|

|

Where Does the Sun Rise and Set?

|

|

Most people know that the

Sun "rises in the east and sets in the west".

However, most people don't realize that is a generalization.

Actually, the Sun only rises due east and sets due west on

2 days of the year -- the spring and fall equinoxes!

On other days, the Sun rises either north or south of "due east"

and sets north or south of "due west."

Each day the rising and setting

points change slightly. At the summer solstice, the Sun rises as far

to the northeast as it ever does, and sets as far to the northwest.

Every day after that, the Sun rises a tiny bit further south.

The rising of the Sun at different places on the horizon at different times of the year

is because the Earth is tilted on its axis.

|

At the fall equinox, the Sun rises due east and sets due west. It

continues on it's journey southward until,

at the winter solstice, the Sun rises as far in the southeast as it ever does,

and sets as far to the southwest.

Many, if not most, prehistoric cultures tracked these

rising and settings points with great detail.

If they had jagged mountains along the horizon, the exact points could be

readily remembered. Without a suitably interesting horizon, standing stones

could be arranged to line up with

the various rising and setting points. Or, tree poles or rock cairns were often used.

|

How does this work?

|

|

|

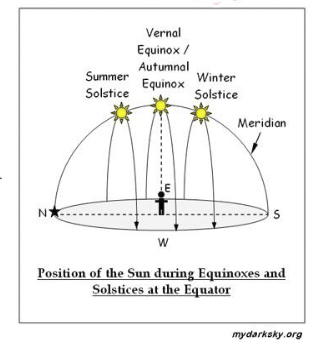

Imagine yourself standing in the middle of the disk in the image above.

And imagine that the outside rim of the disk represents your horizon.

The circles with the Sun above you illustrate where the Sun would be if you were standing at

the equator. Here, during an equinox the Sun would rise due east,

at noon it would always be directly over your head, and it would set directly west.

Because the Earth is tilted, at the summer solstice, the Sun would rise a bit northeast and set

a bit northwest. The winter solstice Sun would rise a little southeast and set a little southwest.

|

Now imagine yourself standing in the middle of this disk. It represents a higher latitude location on the

Earth, someplace like San Francisco.

Now, on Summer Solstice, you would see the Sun rise on your "horizon" at the eastern point of the

longest track. It would follow the track high in your sky, and eventually

set on the western horizon. It would be up for about 17 hours, thus making

summertime days long and warm.

On the Winter Solstice, you would observe the Sun rising at the eastern end of the

smallest track. It wouldn't rise high in the sky, and would be up for only about

6 or 7 hours, making your days short on daylight and most likely cold.

At the Spring and the Fall equinoxes, the Sun would rise due east, at the east end of the middle

track, and set at the west end, due west.

Your days would be half daylight and half nighttime

and you would experience typical warm/cool spring and fall climates.

Notice that you would never see the Sun directly above you unless you lived in the equatorial region.

|

The Sun Track Dioramas

|

|

|

These dioramas simulate the rising and setting points of the Sun,

and its tracks across the sky at summer solstice

(longest track), winter solstice (shortest track), and the spring and fall

equinoxes (center track). A bead placed on one of the tracks

simulates the Sun rising along the eastern horizon, traveling along the sky,

and setting on the western horizon.

The angle of the solar tracks can be adjusted for your own latitude.

|

|

What about the stars?

|

The rising points of the stars don't change as much as the Sun's because

they are so very far away. So the rising points of stars on the horizon were

not as critical to ancient cultures.

However, because the Earth is circling around the Sun, the rising times of

stars change by 4 minutes each day. so

any particular star would rise at different times during the year. Though for

about half the time, the star would rise during the daytime and thus be

unseeable due to the light of our Sun.

However, there is something called

the "heliacal" or dawn rise of a star -- and this happens on only one day of the year.

A heliacal rise is the morning that a star is first seen after being blocked by the summer Sun.

Thus these dawn risings were extremely useful for keeping track of exact days.

|

The Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming is a good example of

a site tracking heliacal stars.

For an explanation and examples of heliacal or dawn risings of stars, see

Show Me a Heliacal Rising.

There is new evidence suggesting that some very ancient cultures may have tracked the rising of

constellations. For an example of this, see

Gobekli

Tepe.

|

Return to Ancient Observatories -- Timeless Knowledge

Image credits:

- Medicine Wheel sunset photograph by Tom Melham.

The Tom Melham picture appeared in the National Geographic.

According to them, it is part of a collection

"Mysteries of Mankind: Earth's Unexplained Landmarks" and the image

is listed

as usuable, with no permission or payment required. Just need to

give credit, which is:

Medicine Wheel sunset photograph by Tom Melham.

- Native American Suntrack Diorama photo and design by Ginger Armstrong, Kelseyville, CA.

- Seasons Suntrack Diorama photo by Ben Buress, Chabot Space and Science Center.

- Suntrack dioramas designed by Deborah Scherrer with help from Philip Scherrer and Barbara Scherrer.

|