Solar and Stellar Alignments

Astronomer John Eddy* became intrigued by the cairns of the

Bighorn medicine wheel in the 1970s.

He discovered that one pair of cairns was aligned to

solstice sunrise and another to solstice sunset.

But he could find no answer for the existence

of the other cairns. They seemed to have a purpose since they

were so prominent. What could it be?

Dr. Eddy began his search with the

sunrises and sunsets of other important dates, such as winter solstice and

the equinoxs but found no correlations. Not easily deterred, he checked for

alignments to the Moon and stars. The paths and cycles of the Moon lead to

nothing substantial.

However, in the stars he found an intriguing correlation.

Because of the Bighorn wheel's location, on top of a high and windy mountain,

the wheel is only accessible for about two months in mid summer.

The rest of the year the wind-swept plateau is covered in snow

and freezing cold. Eddy needed a starting point so he began looking for

stars that were in the sky in the months before and after summer solstice,

when the mountain was accessible.

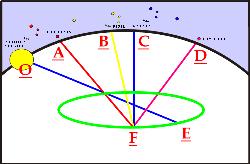

What he found were alignments to three stars during their heliacal risings.

Heliacal risings occur when a star has been behind the Sun for a season,

but is just returning to visibility. There is one morning when the star "blinks"

on before the sunrise.

That one special morning is called the star's heliacal rising.

Not all stars have heliacal risings because some stars remain

above the horizon all the time. Only certain stars rise and flash into

existence in the predawn glow of the horizon. Each day that passes after the

heliacal rising, the star will appear to rise earlier and remain in the sky

longer until its soft glow is obliterated by the rising sun.

Because these helical risings were so specific, just one day,

they were used by many different ancient civilizations to mark specific

events such as the drought season and planting time. It is not surprising

that the Plains Indians would use heliacal risings to signal the coming and

going of the solstice.

Eddy found that three major cairn-pairs had corresponding

heliciacal rising alignments to Aldeberan, Rigel, and Sirius,

three of the brightest stars in the sky.

A later researcher found a cairn alignment for Fomalhaut, another

very bright star. These alignments all

occur from standing and sighting at one specific cairn.

|

The heliacal rising of Aldeberan signals the coming of the summer solstice

in just a couple days. Rigel rises almost exactly one lunar month (28 days)

after Aldeberan and Sirius one month after Rigel.

This could account for for Bighorn's 28 spokes.

The rising of Sirius could be the signal to pack up and leave Bighorn

because the weather was going to take a severe turn. The

alignment of Fomalhaut occurs 28 days before the solstice.

For more details on the astronomical alignments, see

Petroform Astronomy.

What else might the wheels have been used for?

There are many different ideas about the origins of the wheels

and the reasons they were built.

One of the most exciting connections to the wheels is the

Plains Indian Sun Dance.

For many of the Plains Indians, the Sun Dance was their major communal religious

ceremony. Generally held in the late spring or early summer, the

rite celebrates renewal, spiritual rebirth, and regeneration of the living

Earth with all its components.

The ritual involves staring at the Sun while dancing,

sacrifice, and supplication to insure harmony between

all living things. Contemporary Native Americans continue this practice

today.

Some researchers believe that Bighorn closely resembles a Medicine Lodge

or Sun Lodge.

These structures were built out of wood by the Plains Indians for the

their sacred Sun Dance ceremony.

This supposition is supported by the lack of timber in the area where Bighorn

was built. Stone would have been a more abundant building materials.

However, this correspondence does not fit with all medicine wheels since

Bighorn is one of the few wheels that resemble the shape of the lodge.

The heliacal alignments on the Bighorn wheel could be as simply as signifing

the times of year when the weather is suitable for being on the mountain.

The rising of Sirius would hav been the signal to pack up and leave

before the winter weather set in.

We do know that wheels had many different uses and those uses changed over the

years from tribe to tribe. Some of them were used as burial mounds, or

created to mark a special day in history. Some of them point not only to

the Sun but other medicine wheels or natural resources.

There seems to be evidence that some of the wheels were updated over the

centuries to track the slight changes in solar and stellar alignments.

|